Time Travel

TIME TRAVEL

A journey along the historic watchmaking trail sheds light on the tiny miracles of micro-engineering that make Switzerland’s timepieces the best in the world.

By Carol Besler — Photos by Joss McKinley

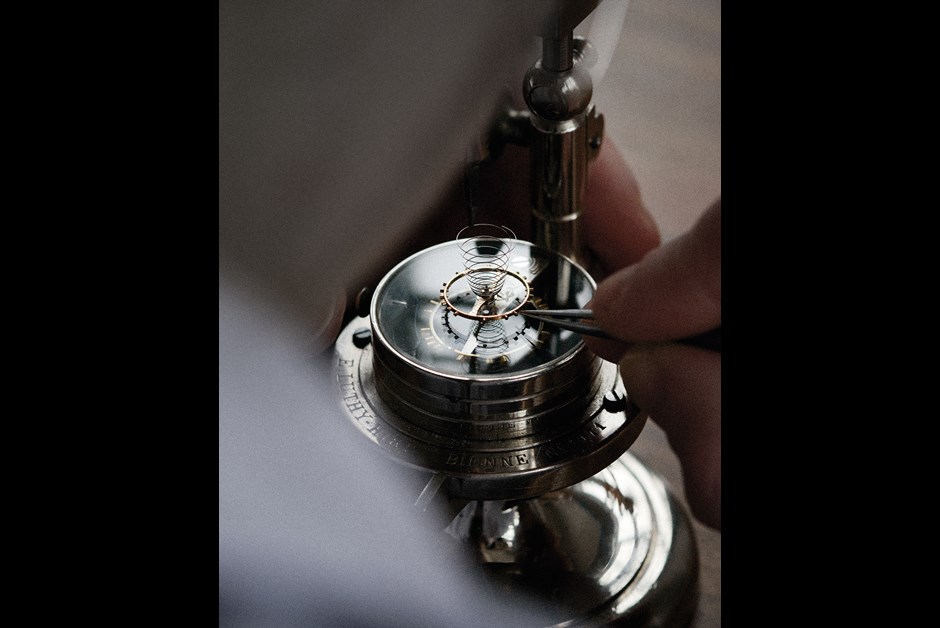

A watchmaker and his work at Montblanc’s institut Minerva de recherche en haute horlogery in villeret, Switzerland

An Horology lesson in the workshop of Lionel Meylan’s Swiss atelier begins with the following advice: “A watchmaker needs four things: good eyes, good nerves, the patience of a saint and,” Meylan concludes, a twinkle in his eye, “good knees.”

True to this insight, my worktable consists of a pair of pin-tipped tweezers, a set of tiny screwdrivers and the impossibly miniscule components required to assemble a movement. A watchmaker, it seems, can spend as much time under his desk as at it. The trick, I discover, is a light touch.

On this bright summer’s day, when most visitors to Montreux are taking in the larger-than-life splendor of Lake Geneva and the magnitude of the Alps, the irony of peering at miniature objects through a loupe is not lost on me. Yet, for anyone drawn to the artisan nature of these tiny mechanisms, there is no more beautiful sight.

For centuries, tourists have come to this swath of glamorous shoreline – known as the Swiss Riviera – in search of pleasure. The Swiss are as renowned for their excellence in the art of hospitality as they are in the art of watchmaking, and Fairmont Le Montreux Palace, a local landmark and my home base for this trip, embodies the area’s luxurious pedigree.

Built during the Belle Epoque as an authentic resort in the old-Europe sense, it was a place where guests stayed for several weeks or months, hiking the Alps’ glittering glaciers by day and dancing in its glittering ballrooms by night. (Indeed, its corridors retain their original 13-foot width, allowing two women in hoop-skirted gowns to pass without touching.)

I am not here for this particular combination of action and glorious inaction, however, but for a special journey into the heartland of Switzerland’s most famous export – mechanical timepieces.

My first stop, Meylan’s workshop, is designed to gain a further appreciation for the precise choreography of a movement, the watch’s counting mechanism. Le Montreux Palace recently partnered with Meylan in response to requests from guests who wanted to learn more about the horology process. Since a good timepiece can easily cost six figures, it’s natural for buyers to wonder what’s under the hood.

Meylan’s workshop offers a glimpse into the mystery. Warning: You really do need the patience of a saint. At one point I mangle the hairspring, the heart of the mechanical movement, which, together with the balance wheel, literally makes it tick. Fortunately I am working on a “practice” device, and Meylan patiently guides me through the process a second time with a new spring.

We are in the midst of what is widely referred to as the second golden age of watchmaking, the first being roughly between 1780 and 1870, when all of the devices of mechanical timekeeping were invented: chronograph, tourbillon, minute repeater (conceived in pre-electricity days to signal the time at night), perpetual calendar, annual calendar. All of them start with the crucial hairspring and balance wheel, known together as the escapement.

The greatest challenge to mechanical watchmaking came in the 1970s and ’80s when quartz watches, driven by a small battery and tiny crystal, nearly killed the craft. Quartz’s low cost and undeniable accuracy made watches more accessible than ever. In the late ’90s, however, a resurgence of interest in the old-fashioned gear-train method of telling time inspired watchmakers to tinker with and reinterpret the traditional mechanisms. This reinvigoration of the craft has resulted in more innovations in mechanical watchmaking over the past 20 years than in the previous 50.

My suite at Fairmont Le Montreux Palace is called Quincy Jones, after the music impresario who has paid many a visit to this quiet sanctuary during Montreux’s renowned annual jazz festival. The expansive room features two terraces, one facing the sunrise in the east, the other the sunset in the west.

I consider this poignant symbol of time as I set off by car to the Swiss Jura, an hour and a half northwest, near the French border. On my approach, the mountains rise up around me as I travel through the green pastures and sleepy mountain villages where watchmaking took hold in the 18th century.

Local farmers, seeking occupation during the long winter months, manned the cottage industry. (Their wives, meanwhile, tatted lace.) The activity gradually migrated to the nearby town of La Chaux-de-Fonds, where, after the entire village burned down in 1794, the Swiss, with their seemingly inborn sense of exactitude, decided to rebuild the town entirely around the craft.

They designed the streets in a grid formation (an anomaly at that time in Europe), in parallel tiers that climb a mountain slope, each street slightly higher than the last, following the angle of the sun as it rose. These terraces allowed the maximum amount of light to penetrate every building for the maximum amount of time – a watchmaker needs good eyes, after all, and sunlight in the pre-electrical age was essential.

Inside, these spaces contained living quarters alongside workshops, each specializing in a particular part: hands, dials, bracelets, movement components. The parts were gathered by an établisseur who issued the orders and then assembled the basic movement in his own atelier.

So successful was this early assembly-line system that nearby Le Locle was later redesigned the same way. By 1915, La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle made half the world’s watches. Compare that with today: While the region now produces only around three percent of the world’s watches, that small portion represents 50 percent of total production value. Many of world’s elite brands, including Cartier, Montblanc, TAG Heuer, Ulysse Nardin and Corum, are located here in modern manufactures.

In 2009, La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle were recognized as UNESCO-protected heritage sites because of this unique industrial-residential integration. If you venture to the 14th floor of the Espacité tower in La Chaux-de-Fonds, you can see a panoramic view of the sloping grid. While some of the buildings are still used as workshops, most are luxurious apartments, with elaborate gardens filling the gaps between rows.

And despite their proto-industrial origins, the buildings incorporate the beautiful flourishes of the Swiss version of Art Nouveau. Style Sapin, or “fir-tree style,” gives a nod to the majestic pine trees that cover the slopes of the Jura and which figure into the decorative motifs of the buildings’ twirling wrought-iron stairwells and the etched glass that punctuates doorways.

Interspersed among the apartment blocks are beautiful villas, the former residences of the établisseurs and factory owners. I tour one of them, the Villa Turque. Designed by Le Corbusier, who was born in La Chaux-de-Fonds and whose father was a watch engraver and enamelist, the villa is now owned by the watch brand Ebel, who maintains it for visiting executives and company events. It is a breathtaking example of Le Corbusier’s form-follows-function philosophy. So exacting are the proportions, it could be considered the bricks-and-mortar embodiment of the Swiss watchmaking ethos.

I experience another example of Swiss precision in the evening at Fairmont Le Montreux Palace’s Willow Stream Spa, where my entire body is thoroughly scrubbed and polished using a pumice combined with that most emblematic example of Swiss flora, edelweiss (or “cloud flower,” as the locals poetically refer to it because of its delicate, silvery white leaves).

Afterward, I dine in La Brasserie du Palace on fresh perch fillets caught that day in Lake Geneva, which, from my table, appears inky-black in the moonlight. There should be a ceremony for this. A celebration of the fish, or perhaps of the fishermen who, like clockwork, rise before dawn to take their boats out onto the lake. I see them at sunrise from the east terrace of the Quincy Jones Suite.

I return the following day to La Chaux-de-Fonds to tour the Musée International d’Horlogerie. The museum’s 4,000 watches and wall clocks, arranged in sequence, span the entire history of movement development. The early pieces are large and awkward. Over time they become smaller and less decorative, but vastly more complex.

This historic visit sets the tone for the final stop on my journey: the Montblanc-owned Institut Minerva de Recherche en Haute Horlogerie. While most watch manufactures are now highly automated, using robotic machines to punch out parts to the tenth of a micron, Minerva continues to produce all of its components by hand.

Here, highly skilled craftsmen fashion only a few hundred timepieces a year, using customized tools based on those from centuries past. Each watch is slightly different and therefore custom. Most are presold to collectors.

I look on as one craftsman puts the final polish on a tourbillon bridge using an unusual tool, the stem of the gentian flower, which grows in the nearby mountain pastures. Its softness and flexibility allow it to reach places no automated polishing machine could ever go. I peer over the shoulder of another craftsman manning a kind of roller, and see that he is, in fact, stretching and coiling long wires into hairsprings for the movements.

Very few manufactures make their own hairsprings; instead they order them now from automated factories that specialize in this component. I flush to witness this painstaking process in action, remembering the botched spring from my own horology experiment.

Alone in the car on my return to Montreux, it’s wonderful to think of the artisans of this city making a hairspring the same way for centuries – and creating the pieces that measured the seconds, hours and years of their lifetimes as today’s craftsmen are fashioning the metronomes of ours. It’s as though, in their pursuit of the most precise and elegant way to tell time, Swiss watchmakers have made it stand still.

Clockwise from top left: horology lesson at meylan’s; a montblanc craftsman bevels a tourbillon bridge; parts and fittings; the 12th-century chillon castle on lake geneva

Clockwise from top left: flower stems are used as polishing tools; watchmaking implements resemble those of a century ago; style sapin doorway at fairmont le montreux palace; antique minerva dial belle epoque flourishes meet contemporary design at fairmont le montreux palace

Concierge

Montreux, Switzerland

Stay Fairmont Le Montreux Palace is a stately wonder on the shore of Lake Geneva. Freddie Mercury lived here; so did Vladimir Nabokov. For a special experience, book the Quincy Jones Suite with east- and west-facing private terraces from which you can catch both the sunrise and the sunset. fairmont.com/montreux

Dine La Brasserie du Palace is decorated in the Belle Epoque style, in keeping with the architecture of the hotel itself. The menu features a combination of authentic Parisian brasserie dishes and Swiss specialties, including fresh perch from Lake Geneva and traditional Alsatian choucroute.

Restaurant La Cheminée, located in a historic former farmhouse in La Chaux-de-Fonds that was built in 1703, has a romantic dining room where regional dishes, including locally raised meat, are prepared over an open grill. lacheminee.ch

Do Participate in the various steps of disassembling and assembling a watch movement as part of The Meylan Watchmaking Experience, under the supervision of Lionel, Yannick or Julien Meylan, resident father-and-sons watchmakers located in the town of Vevey. Visits are by appointment only, so book your experience through the concierge at Fairmont Le Montreux Palace. lionel-meylan.ch

Walking tours of La Chaux-de-Fonds start at the Espacité tower, in the center of the city. One focuses on the symbiosis of watchmaking and town planning. Another follows the Le Corbusier Trail to the architect’s famous designs. There is also a tour focusing on Style Sapin, the art nouveau movement of the region. La Chaux-de-Fonds also features the world’s largest watch museum, Le Musée International d’Horlogerie. chaux-de-fonds.ch