Twist of Fate

By: Eve Thomas

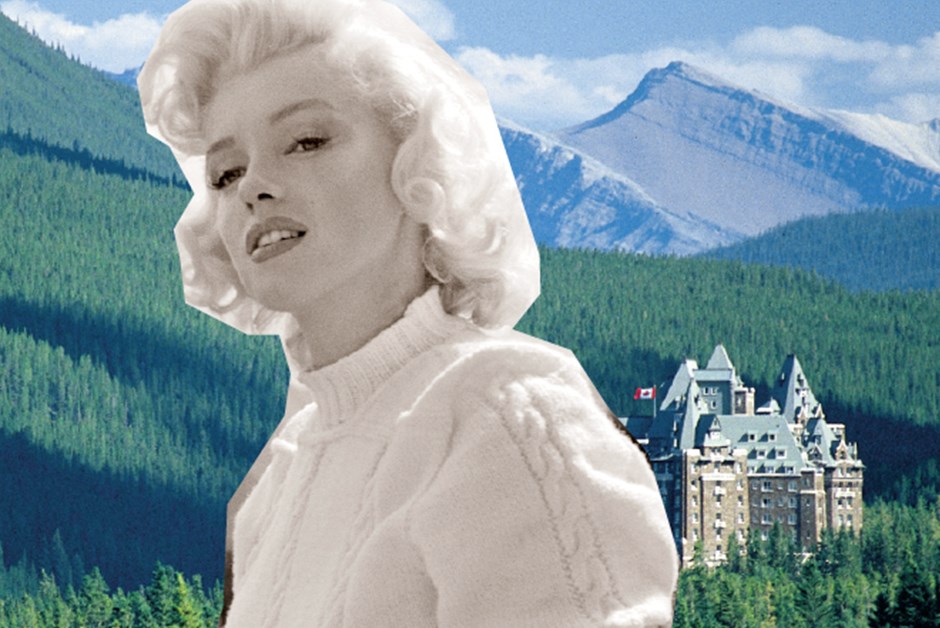

While filming in the Canadian Rockies, Marilyn Monroe turned an injury into an opportunity to recover in style. Head to Banff, Alberta to follow in her (careful) footsteps and explore the enduring allure of natural beauty.

What continues to captivate us so? Is it the small-town charm, the dizzying curves, that ethereal glow?

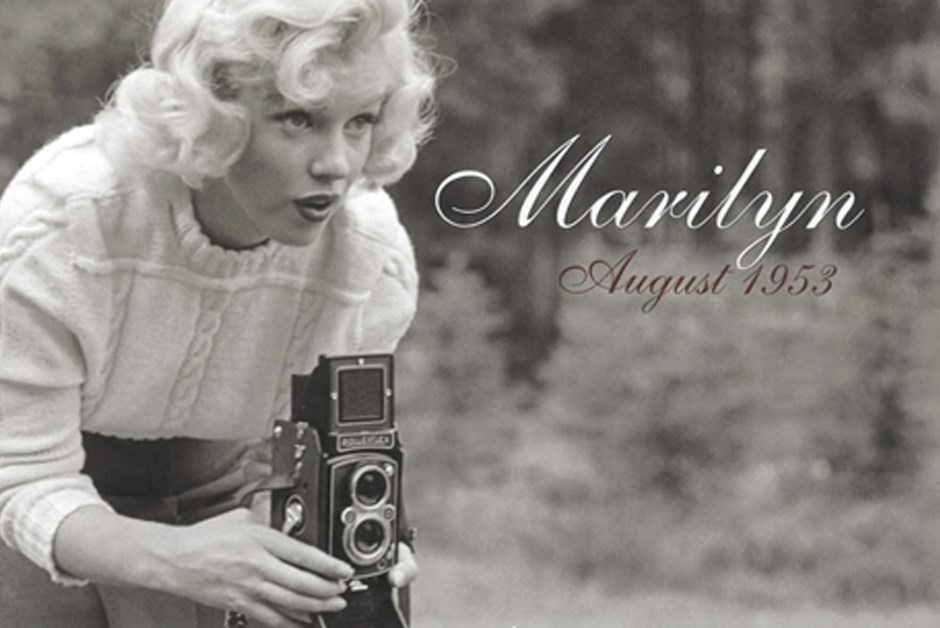

As I pull into Banff, Canada, it’s impossible to choose the more entrancing vision. Out the window, spruce trees and snow-capped mountains reflect in a river so blue it looks airbrushed; next to me, on the passenger seat, lies a book of black-and-white photographs simply titled Marilyn, August 1953. Its kittenish cover model stares ahead intently, lips parted, face framed by a halo of golden curls.

Traveling to Banff to bask in its natural beauty is nothing new. People have journeyed here for the views, hiking and healing thermal springs since the Canadian Pacific Railway first set down tracks in the late 1800s. But my trip is for acquainting myself with another natural beauty: Marilyn Monroe.

Sixty years ago, the actress found herself in this very spot, teetering in heels outside the Banff Springs Hotel, on the brink of superstardom, here to shoot River of No Return. While Otto Preminger’s western about a widower, his son and a saloon singer on a journey down a raging river garnered some acclaim, the general consensus was that the Canadian Rockies deserved top billing, with even Marilyn telling Variety that the “acting finished second to the scenery.” (When CP Railway president William Cornelius Van Horne quipped, “If we can’t export the scenery, we’ll import the tourists,” in 1886, he clearly hadn’t counted on Technicolor cinema.)

It wouldn’t be the first time Mother Nature and Marilyn shared the big screen. The 1953 film noir Niagara had the New York Times proclaiming, “[B]oth the Falls and Miss Monroe are something to see.” That year also saw the release of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire, the titles that transformed Marilyn from movie star to the most enduring Hollywood icon of all time.

Though her life was cut short less than a decade later, we’re forever reminded of Marilyn’s timeless appeal: made-for-TV movies, auctions of her Pucci dresses, pop stars posing in flaxen wigs and faux beauty marks.

In fact, it often seems there is little left to reveal of Miss Monroe.

So the buzz was understandable when, in 2010, over a hundred revealing images were released – the “lost,” previously unpublished photos shot by John Vachon for LOOK magazine. The collection proved to be as much of a testament to the beauty of Banff as to the timeless appeal of Marilyn Monroe, with nary a bad angle between them.

Used to snapping stark, Dorothea Lange-style portraits of everyday Americans, Vachon wasn’t sure what to make of his editor’s assignment, “Hollywood Comes to Canada.” (Two other westerns were shooting in the Rockies that summer, and all made the Banff Springs Hotel their base.) In a series of letters to his wife, the photographer scoffed at the star system, including the elaborate entourage that made getting time with Marilyn a feat.

Then came the news. She’d hurt her ankle, first while shooting in Jasper National Park, then again by Banff’s Bow Falls. “Marilyn Nearly Drowned!” blared a local paper. But, for Vachon, the injury proved a stroke of luck. At last, Marilyn had time to pose, crutches and all.

When they finally met, the photographer surprised himself – he was instantly fond of the starlet. Vachon found Marilyn “friendly” and “sweet,” delighting in the down-to-earth charm beneath her glamorous veneer. (Of the hotel itself, he joked to his wife that it was “really magnificent, if you care for this sort of thing.”) While only three shots of Marilyn made it into LOOK, Vachon’s outtakes offer a precious glimpse at her sillier side: In one set, she ascends a mountainside by chairlift – a tiny, ricketylooking thing – waving like the Queen of England. In another, she tees off on the Banff Springs golf course in a pencil skirt and Ace bandage. She seems happy to camp it up for Vachon’s editors, whether readjusting a Mountie’s uniform or pouting lamely by the swimming pool.

In the most unguarded moments, Marilyn poses by a window with her soon-to-be husband (they divorced in 1954), Joe DiMaggio, something the baseballer rarely allowed. She’s at once nervous and goofy, making faces in one shot, looking wistful in another. Even in shades of gray, the picture-perfect mountaintops provide a striking cinematic backdrop, and once again it’s difficult to know how to divide my attention.

“Every morning the bellhops flipped coins to see who got to push her in a wheelchair,” says hotel historian and guest relations manager David Moberg as he leads me through the Rundle Lounge, where guests are settling in for traditional afternoon tea. If anyone holds the keys to the past at The Fairmont Banff Springs, which celebrates its 125th anniversary this year, it’s a man who has been working here for half a century. As Moberg leads me past yet another stunning view of the valley, I’m reminded of what Otto Preminger told a local newspaper while scouting locations: “I guess it doesn’t matter where I point the camera.”

With each step (and barely a pause) Moberg reveals the secrets of every nook and cranny, from the glass-topped Conservatory, the first cocktail lounge in the province, to the water tower-turned-Royal Suite. In one hallway, he stops and motions behind him, lowering his voice conspiratorially: “When Ginger Rogers returned to the hotel in blue jeans after 6 o’clock, she was arrested and escorted up these fire stairs.”

Marilyn Monroe wasn’t the only famous face to grace the hotel. Silent film star Mary Pickford, Alfred Hitchcock, Indira Gandhi and the first reigning British monarchs to visit Canada, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, have all checked in. Bing Crosby and Bob Hope headed straight for the golf greens. Winston Churchill was inspired to paint the Bow River. Today’s guests might spy Alec Baldwin or Peter Fonda in the lobby, here raising money at Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s annual Waterkeeper Alliance celebrity ski event.

“I could name drop till the cows come home,” says Moberg, “but it’s not about them. It’s about the people who choose to come here, who’ve crossed four time zones for that special occasion or that once-in-a-lifetime trip.”

Still, when the guests on Moberg’s heritage tour – the honeymooning couple from Korea, the family from Australia – hear the M-word, their faces light up.

More than half a century later and she’s still the most famous person to pass through Banff. If most of us know a Marilyn Myth – she only listened to Beethoven, she had a hot fudge sundae every night – then the Fairmont staff and Banff’s 8,000 permanent residents know even more – she had a limo on-call 24 hours a day, she borrowed a local boy’s bicycle and took off, unnoticed, for the day. Later that afternoon, my cab driver points me to the street where she supposedly stopped traffic, and to the spot where she fell in the river. And when her name comes up at a souvenir store off the main strip, an elderly woman in line hums, unprompted: “There is a river called the River of No Return, sometimes it’s peaceful and sometimes wild and free…”

“A few years ago we had a big exhibit in the museum and then just a little display on Marilyn Monroe, a collage, but all the papers reported was Marilyn,” recalls Lena Goon with playful exasperation. Goon has been buried in Banff’s past for 30 years working in the archives at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, and when she’s not helping visitors research glaciers and mountaineers she’s showing them movie memorabilia: posters, articles (“Fasten your seatbelts, boys. Marilyn Monroe is coming to Banff next month!”), shooting scripts, fanclub newsletters, snapshots taken by citizen paparazzi.

Digging deeper, one more facet of Marilyn reveals itself. (As ever, it’s not wise to underestimate her.) It turns out that her ankle injury may not have been that bad. Rumors circulated that it was she, not her doctors, who insisted on a cast. That it was all a ploy to get some sympathy from a notoriously demanding director or to take revenge against a movie studio that had her locked into a low-wage contract.

But I’ve formed my own pet theory about Marilyn’s time off. It crystallizes as I make my way up Sulphur Mountain by gondola, as the town fades into the trees.

Injury or no injury, minor or major, perhaps Marilyn simply wanted to gain some perspective before heading back to Hollywood, to the career – and the fate – that awaited her. Maybe it was all an excuse to sit back and take in the scenery: the glittering peaks, the glacier-fed lakes, the crisp mountain air.

It’s enough to make anyone want to play hooky for the week.

(Photos of Marilyn Monroe by John Vachon)