A Royal Affair

By: Natasha Mekhail

Journey to Jaipur, India’s historic land of kings, for a modern revival of the most regal traditions.

The fort’s heavy doors open to a lantern-lit courtyard. As I step from the car, an attendant in a glittering green tunic receives me with a bow, his hands clasped in greeting. Trumpets blare and my eyes shoot up to the second-floor arches in time to catch two turbaned men lowering their instruments and retreating from view. Now a woman in sari approaches, padding softly across the stone floor to anoint my forehead with a dot of sandalwood paste. She leads me through a second courtyard, the fountain at its center encircled by a mandala of rose, jasmine and marigold petals. Inside, the music I’d thought piped through speakers is revealed as coming from an actual sitar, its player plucking briskly on a low cushioned platform.

I haven’t even reached the reception desk.

This is the maharaja’s welcome that awaits every guest to Fairmont Jaipur. In this reimagined Mughal fort, the newly opened hotel tells the story of India’s past. Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan, is the ancient domain of royals, legendary for their luxurious excesses and worship of beauty. But this 21st-century palace, equipped with every modern comfort, also tells the story of India’s future: a country of emerging prosperity quickly realizing that, in the same-old-same-old of globalization, India’s attention to detail and flare for ornamentation are precisely what sets it apart.

Where else would it still be possible to find, in a single city, the 1,000 local artisans who worked for five years to paint Fairmont Jaipur’s intricate murals, carve its wooden window screens, restore its antique doors, sculpt its stone elephants and craft its camel-bone-inlayed furniture? Skills lost centuries ago in the West are, here, still very much alive, honed by generations and influenced by contemporary tastes.

To a weary traveler, the first impression is one of absolute splendor. As I finally slip into my four-poster bed under the watchful eye of a wooden parrot (a feature in every room and the historic companion of royalty), it’s hard not to feel like those kings and queens of India’s past.

Next morning has me following in their royal footsteps as I venture high in the pink Aravalli hills outside Jaipur to the imposing Amber Fort. In spite of the tranquility this walled palace once concealed, it represents a period of turbulence. The warring nature of northern India’s 16th-century princely states (some Islamic Mughal, some – as in Amber – Hindu Rajput) required the royal family to take up residence in these fortifications. It wasn’t until 1727 that more peaceful times brought Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II down from his hillside retreat to found the city of Jaipur.

My guide, Raj Singh from Abercrombie & Kent tours and a descendent of the Rajasthan nobility, directs me through the former palace, describing the lives of those who lived here: the maharaja and his family in one quarter, his dozens of wives and concubines in another.

As Singh sets the scene, I imagine what a magical place it would have been. Its colored frescoes with gold-leaf accents covering every wall anddomed ceiling. The ladies’ pleasure garden landscaped to resemble a Persian carpet. The richly adorned tents, mattresses and cushions that would have provided places of quiet repose to the fort’s noble residents. Singh tells of the moonlight parties on rooftops, of the dances maharaja watched from a sandalwood swing, of the intimate rendezvous orchestrated through a network of secret passages.

He shows me the Sheesh Mahal, the crystal chamber, its walls and ceiling studded with thousands of mirror fragments. “A single candle made the hall look like twinkling stars in the night sky,” he explains with a smile that says his ancestors’ lavish desires knew no bounds.

That Indian predilection for ornamentation wasn’t limited to nobility. The driver carries us into Amber village, where the maharaja’s subjects would have lived without the protection of fortification.

We’ve entered the people’s India. Psychedelically painted trucks blast their horns as cars and motorcycles jostle around them. They share the road with pigs, camels, goats, the odd saddled elephant and a seemingly endless procession of slow-moving cows, whose sacred status awards them a kind of cosmic diplomatic immunity. It’s here that we find the Anokhi Museum of Hand Printing, a 16th-century haveli, or manor house, turned education center for the local craft of block printing.

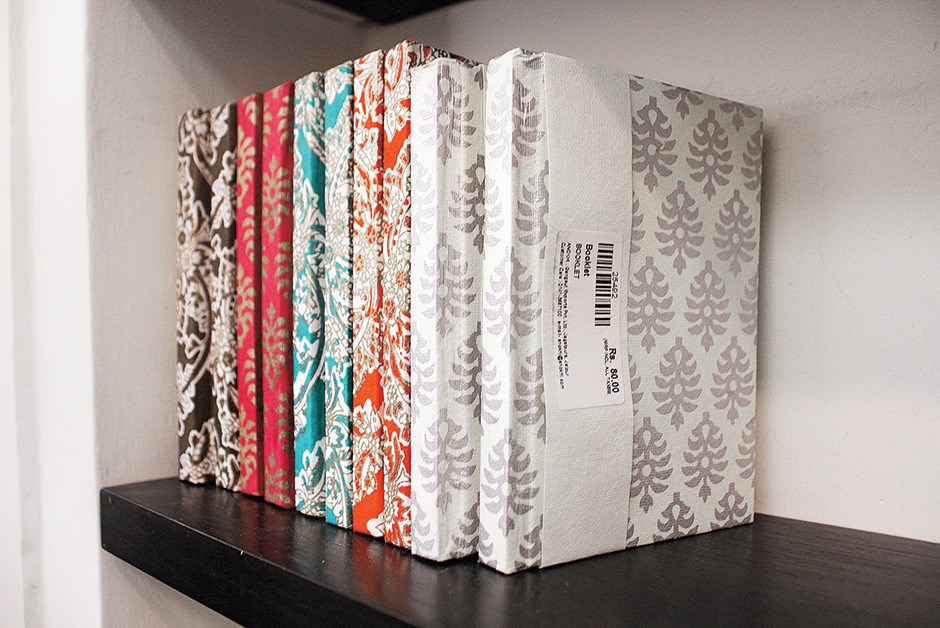

Historically, block-printed garments were used as a means of identification. Caste, age and even marital status were reflected in the colorful patterns on clothing, with the most intricate work reserved for royalty. The process divides roughly into three specializations. One group of artisans tends to the dyes – indigo for blue, madder for red, turmeric for yellow. The second group carves stamps of complex flower, paisley and dot patterns from blocks of teak. A third specializes in the printing of the fabric, stamping the material time and again and laying down layers of color.

We watch block cutter Mujeeb Khan deftly carve a perfectly symmetrical design. Speaking though a translator, Khan reveals he’s been cutting for 35 years and learned the skill from his father. None of his own sons plan to follow suit, however. “They are all going into computers,” he says with a mixture of pride and sadness.

John Singh and his English wife Faith founded Anokhi (literally “unique”), which designs block-printed garments and accessories, in 1969 after falling in love with this tradition from Rajasthan. They’ve since passed the business on to their son, Pritam, and daughter-in-law, Rachel, who in turn founded the Anokhi Museum of Hand Printing in 2005 to strengthen appreciation for this art form.

The Singhs realized long ago that between the westernization of clothing, the digitization of printing and a lack of young people taking up the trade, this beautiful art would simply vanish unless a way was found to make it relevant.

Today they employ printers from villages around Jaipur at fair wages. On a farm on the city’s outskirts, they manufacture stylish, of-the-moment clothing from block-printed fabric, which they sell in their trendy boutique in Jaipur’s upscale C-Scheme district, as well as at 22 other locations across India.

Anokhi is just one example of the efforts underway to revive the country’s textile arts. For its fifth anniversary in October 2012, Vogue India staged Project Renaissance, a collaboration that paired some of the world’s top design houses with India’s textile makers (think a Burberry trench crafted in Maheshwari silk, Ferragamo pumps swathed in Benarasi brocade and Hermès’ classic Brides de Gala scarf recreated by Bengali embroiderers).This project was not just a one-off, but a calling of attention to luxury brands entering the Indian market. Designers like Gucci already incorporate dedicated Indian pieces into their collections and Hermès released its first line of saris in 2011. It’s also a recognition that the quality, craftsmanship and painstaking detail that India prides itself on are precisely in line with the ideals of haute couture.

Similarly, India’s obsession with jewelry is taking hold here and abroad. Since the days of Jai Singh II, precious stones have been polished, cut and set in the city. Even today Jaipur contributes 80 percent of India’s gem and jewelry exports.

Focus, time and an appointment are prerequisites when visiting the showroom of Amrapali jewelers in C-Scheme. Glass cases stretch from floor to ceiling, packed with elaborate sparkling pieces in diamonds, emeralds and rubies. Row upon row of bangles, necklaces and earrings dangle from racks down the center of the shop, creating dazzling visual chaos. In the 1970s, Amrapali’s founders, Rajesh Ajmera and Rajiv Arora, two former history students, traveled the country seeking out vintage pieces. By the end of the decade, they had amassed such a collection that they opened a shop to showcase their finds and create new designs, a venture that has since grown to 36 outlets and a team of 1,200 craftspeople.

Their one-of-a-kind pieces are highly coveted worldwide, as a phonebook-sized portfolio of celebrity clients (from Angelina to Zeta-Jones) in the showroom attests. And as company codirector Anil Ajmera tells me, his fingers glinting with stacks of architectural rings, it was the Indian jet set who brought this aesthetic to the world. “As people made more money and began to travel outside of the country, they realized how special their own jewelry was,” he says.

I gravitate to the oversized chandelier earrings, made of tinkling squares of gold, and to the rings set with uncut diamonds in the Mughal tradition. The raw asymmetry of the stones is surprisingly contemporary.

The sun is low in the hills as I venture back to the hotel through Jaipur. Jai Singh II’s fascination with vastu shastra (the Indian canon of architecture, similar to feng shui) informed the design of his gridded metropolis.

The streets pulsate with the rhythm of daily life: people visiting sweet shops and market stalls; women buying strings of marigolds; men sipping tea outside tobacco stands; bikes, cars, carts and rickshaws zooming around the central roundabout while pedestrians weave miraculously through the fray.

At the hotel, I find tradition and modernity in equal parts. The clean lines of Anjum, the British Colonial-themed lobby tearoom, culminate in double-high windows that peer out onto a reflecting infinity pool. Beyond it rise the white domes of the 14,000-square-foot (130-squaremeter) Willow Stream Spa, an outbuilding of the hotel slated to open this fall. Illuminated by spotlights, it evokes a mini Taj Mahal.

Over dinner, I indulge in another aspect of new India: a crisp sparkling wine from the grape-growing Nashik region. The meal at Zoya, one of Fairmont Jaipur’s two restaurants, is comprised of Rajasthan specialties. Chef Anurag Bali embarked on a 1,250-mile (2,000-kilometer) road trip through its country villages, discovering local dishes and collecting family recipes. His menu reflects the deepest appreciation for flavors that exist nowhere else but here.

Now it’s my turn to appreciate as I bite into a succulent morsel of laal maas lamb in a chili-yoghurt sauce. In this modern dining room, where I’m seated beneath a silk canopy (a modern take on a maharaja’s tented camp), it’s clear that India is embracing the future, yet I can’t help but be happy that there are those determined to capture and preserve its past.

(Photos by Tina Chang & Guillaume Brière)