Nouveau Monde

Nouveau Monde

Beyond the 17th-century facades of Quebec City, Canada, a modern metropolis is emerging with all the architecture, culture, nightlife and dining to match – and while the tone is strikingly contemporary, it nods proudly to the past.

By: Valerie Howes

Photos by: Lorne Bridgman

Styling by: Cary Tauben

The first time I stayed in Quebec City, at Fairmont Le Château Frontenac, was 16 years ago, with my son – then a toddler. We walked the cobbled streets of the Old Town. I practiced my French at European-style bistros by ordering lacey crepes. And we visited the Plains of Abraham (once a battlefield, now a public park), until he’d announce – like a petit prince in snow pants – “I want to go back to my castle.”

The desire to inhabit a 121-year-old hotel orbited by 17th-century fortifications is a regal dream even for those more than three feet tall. Quebec City is one of Canada’s oldest settlements, and the Château, with its copper roof and fairytale turrets, the jewel in the city’s crown.

French explorer Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec City, in 1608, as a fur trading post and the first permanent colony of New France – a territory stretching west from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains, and south from subarctic Hudson Bay to the mouth of the Mississippi.

The French and British clashed repeatedly for control of Quebec City; the capital of New France was a key trading port on the St. Lawrence River – the most important commercial waterway in Canada to this day. To protect their strategic position, 18th-century French leaders built more than three miles (five kilometers) of fortifications around the Old Town, which today is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Yet the British still laid siege in 1759, claiming victory in a 15-minute battle on the Plains of Abraham, which brought French rule across all North America abruptly to an end.

Still, the language and culture prevailed. In the late 18th century, to calm tensions between French Canadians and the influx of Loyalist subjects fleeing the American Revolution, the British created Upper and Lower Canada, with Quebec City as Lower Canada’s capital. This laid the foundations both for the predominantly French-speaking province of Quebec and, ultimately, for Canada as an independent country.

So while history may be palpable here in every cobbled step, locals refuse to treat their hometown like a city frozen in time. On returning to stay at the newly renovated Château this year, I discover a dynamic and youthful Quebec City, crying out to be explored.

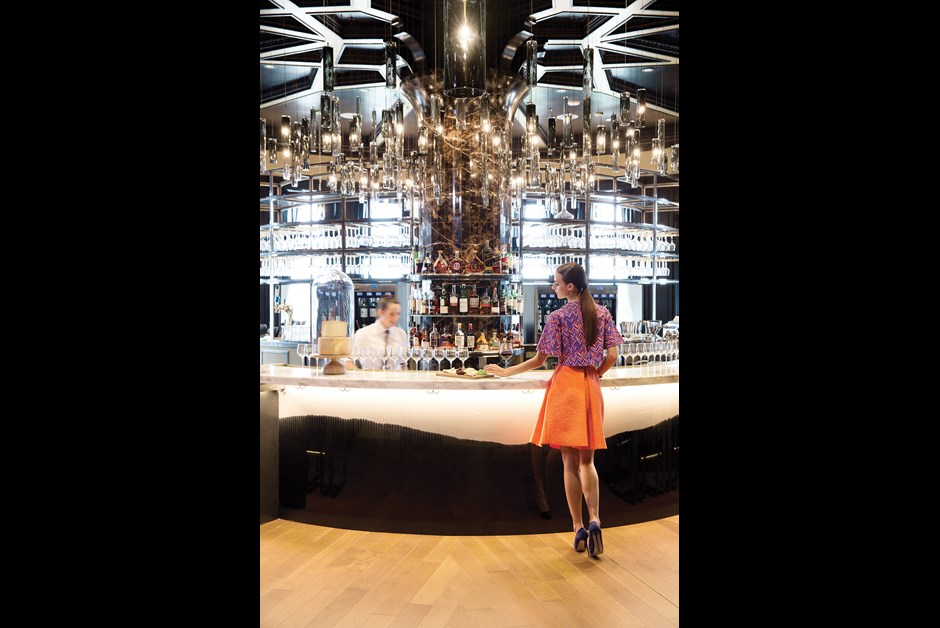

I settle into a bronze bar stool at the black marble bar in Bistro Le Sam, under a light fixture of gold and copper strands, as delicate as fine-chain necklaces. Their colors complement the plush blue velvet and pale gold of the booth seating around me. My bartenders are Joannie, who does a wee shoulder dance as she mixes drinks, and Daniel, who sports a Tintin haircut and thin beard. They explain that the decor was inspired by the vintage passenger cars run by Canadian Pacific Railway – the company that built the Château and many of Canada’s historic hotels to accommodate 19th-century rail travelers. The name Le Sam pays homage to the city’s founder, Samuel de Champlain, but in cheeky diminutive to point out its smart-casual ranking among the hotel’s three new restaurants.

Built on Cape Diamond, a quartz-encrusted cliff overlooking the city, where for 200 years the territorial governor's residence once stood, the Château has been the backdrop to daily life since 1893 and has hosted such dignitaries as Grace of Monaco, Winston Churchill and Charles

de Gaulle. It was even the silent star of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 thriller,

I Confess. All of these elements of the Château’s storied past inform its latest incarnation.

I ask Joannie for a cocktail suggestion from the new menu and she returns with a Martinez. Warm with cinnamon and allspice bitters, it’s served in a slightly misshapen silver tankard. “This thing has been at the Château for a very long time,” she says.

For my next drink, Daniel pumps bourbon-barrel smoke into his cocktail, then covers it with a glass cloche. “This is our spin on the classic Bijou, which uses gin to represent diamonds, sweet vermouth for rubies and Chartreuse for emeralds,” he says. “But ours is called the Algonquin because the smoke suggests the campfires of Quebec’s first inhabitants.”

When Daniel lifts the cloche, dramatic swirling ensues. Then each time I raise my stemless glass from its base, it sends out a tiny smoke signal. A couple approaches just to stare. Who doesn’t like barside theatrics?

June marked the completion of Fairmont Le Château Frontenac’s facelift, a renovation that touched on everything from the guest rooms to the spa. In the lobby, the original oak paneling and gleaming brass mailbox and elevator doors that I remember remain. But behind the reception desks I now find backlit blue-rippled Italian onyx and ultramarine ceiling panels, recalling the St. Lawrence River – the city’s lifeblood.

This motif continues in the more formal Champlain Restaurant, where a twisting swath of gauze streams across the ceiling. Breakfast is just wrapping up as I sit down for coffee with the hotel’s executive chef Baptiste Peupion and Champlain Restaurant chef Stéphane Modat.

“We hear a lot about Nordic countries right now. Why not Quebec?” says Peupion, an Alain Ducasse protégé. He and his second-in-command are in whites, sans toques, on a break before their lunchtime shift. One picks up where the other leaves off, like an old married couple, as they define their vision for a new Quebecois cuisine.

“We use what Quebec has now instead of looking backward to what they had in a time before trading,” says Modat. “For example, coconut may not be a terroir product, but everyone’s grandmother here used it in their macaroons. It belongs to our culture.”

“And maple syrup is great, but there’s so much more,” adds Peupion. “A local company, La Face Cachée de la Pomme, is making us ice cider from the juice of apples frozen on the branch in winter,” continues Modat. “It’s a great example of what people call a terroir product, but if you look back 30 years, it didn’t even exist.”

As well as working with traditional imports and customized artisanal goods, the young chefs also favor regional delicacies – sweet little strawberries from across the bridge in Île d’Orléans… fresh lobster caught from the Magdalen Islands… artisanal charcuterie from the farms of the Gaspé Peninsula on Quebec’s eastern tip.

In the glassed-in cheese room of the hotel’s new 1608 Wine & Cheese Bar, one of the signature products is cheese made from the milk of the Canadienne. The stocky cow was the only dairy breed to have been developed in North America. It almost disappeared in the 20th century. But its milk is luxuriously rich, and the animal thrives in Quebec’s frigid winters, so a few farming families in the province have been working to save the Canadienne and elevate its reputation to prized terroir breed. “If we don’t lead the way by offering products like this,” says Peupion, draining his coffee, “who will?”

Approaching the 19th-century Saint-Esprit church in La Cité-Limoilou – amid a modern throng of cafés, bikes and strollers – I know I’m in the right place when I catch a girl singing loudly on the front steps and practicing a Charlie-Chaplinesque choreography. She’s the class clown (literally) of École de Cirque de Québec circus school. I push open a heavy wrought copper door beneath an electric-lime big-top-like canopy, step inside and take a pew.

Downstairs, beneath a sapphire vaulted ceiling, I find girls pedaling unicycles where choirboys once clasped hymnbooks. “Mind if I watch?” I ask. Pleased to have an audience, they take things up a notch, adding backward moves and 360-degree turns.

From its founding, Quebec City was predominantly Catholic and home to several religious orders. In the 1950s, religion and politics went hand in hand, with priests not only preaching religion but also trying to sway churchgoers in the vote. Prime Minister Duplessis’s era of religious oppression and regressive politics came to be known as the Great Darkness.

By the 1960s, a new generation was rebelling against the old regime, investing their energy in progressive social change and the arts. Church

attendance plummeted.

Today, Quebec City has 130 churches, 20 convent chapels, two cathedrals and two basilicas, all considered architectural and cultural treasures. Faced with the demise of these assets, the Archdiocese has been working with the Ministry of Culture and Communications to preserve properties like Saint-Esprit, giving them new uses – but ones that keep them at the heart of community life.

Upstairs, I watch a teenage boy in tights slither through a hanging hoop, stained-glass windows in the background. His female mentor calls out advice when the boy’s body gets stuck in a pretzel form. I ask another girl why she comes here as she clambers onto a trapeze. She calls back, kicking her legs to swing, “Cirque du Soleil!”

My calves are getting a killer workout as I explore this city of uphill climbs on a BMW Cruise Bike that I borrowed from the Château. I pedal past the fortifications toward the Plains of Abraham, heading over to the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, a onetime prison, now home to the province’s collection of fine art.

Builders are constructing a pavilion for large-scale exhibits in an architectural collaboration between Dutch luminary Rem Koolhaas’s firm and Montreal’s leaders in sustainable design, Provencher Roy. Architectural renderings reveal a glass pavilion that will be seamlessly integrated into the park and bathed in natural light – the Quebec City equivalent of the pyramid at the Louvre.

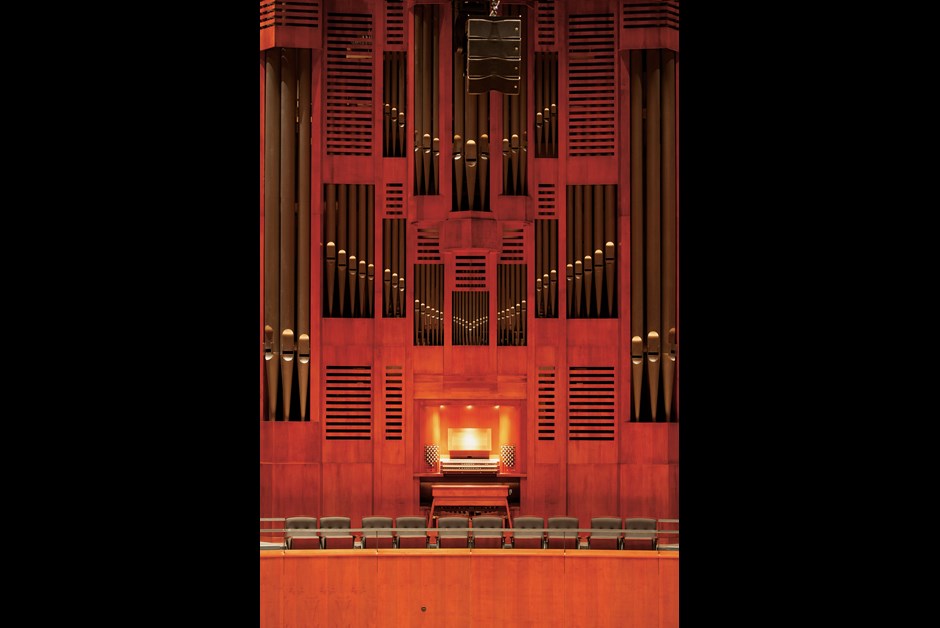

This synthesis of modern design with the strongholds of Quebec City’s past has created some creative architectural workarounds, such as Les Musées de la Civilisation’s stone-and-glass frame that climbs the sloping bank of the St. Lawrence, and the Palais Montcalm, in which an ultra-modern acoustic hall was fused to the building’s existing Art Deco facade.

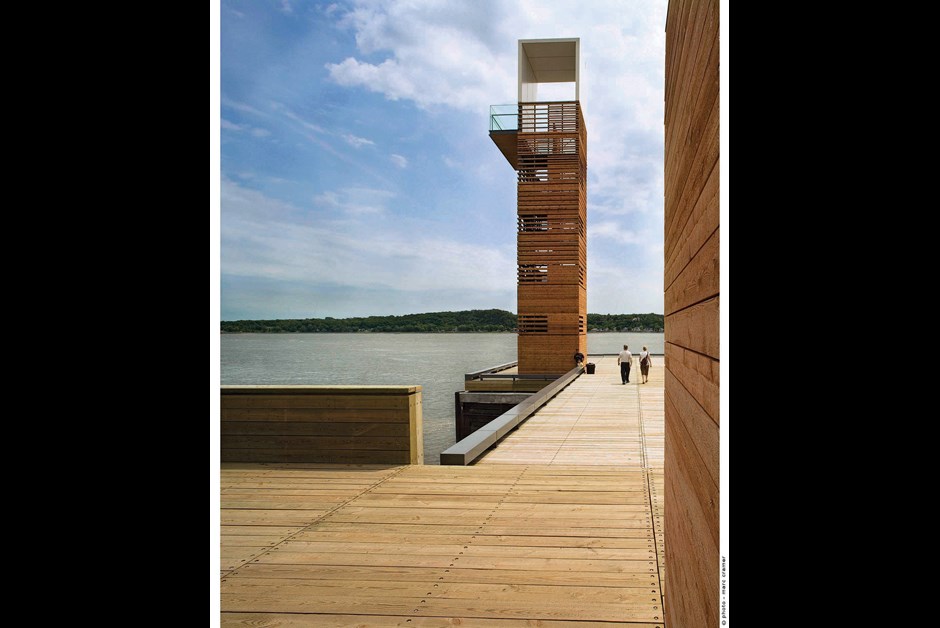

To see more, I take the cycle path past the Plains’ now-silent cannons and pick up speed as I descend the winding streets down to the Old Port to reach the Promenade Samuel-De Champlain – a 1.5-mile (2.5-kilometer) public path that follows the St. Lawrence River. Inaugurated for the city’s 400th anniversary in 2008, the very visual riverside trail is punctuated by modernist rest stations and large-scale public artworks. Its highlight is a modern lookout tower, the kind of minimalist structure on which beautiful people linger in the pages of Dwell (but here set in a locale where fur traders once launched their canoes).

On my way back, I stop to photograph Canadian Prairies sculptor Joe Fafard’s powder-coated, cut-steel-plate abstract sculptures of horses. The eight vividly colorful and heroic-sized galloping ponies were a gift from the City of Calgary, Canada, whose farming and lumbering industries were built on the labor of horses sent west from Quebec – horses whose ancestors crossed the ocean from the French stables of King Louis XIV.

Their poses are said to represent past, present and future. The vitality of their arched necks, flying manes and pounding hooves certainly speaks to the new Quebec City I’ve discovered on this trip. I sit down for a while to take it all in.

My son, now getting ready for college, would have loved the energy in this city. I send him a snapshot of Fafard’s horses and a wish-you-were-here text. It’s getting late. I’ve been cycling hard. I want to go back to my castle.