Baku

ArtS on FirE

Ignited by architecture's biggest stars and a nascent art scene, Baku, Azerbaijan, is ablaze with possibility.

By Ellen Himelfarb — Photos by Gunnar Knechtel

In an otherwise quiet dining room in Baku’s cobbled old city, Farhad Khalilov and his son Bahram, deep into their third glass of shiraz, are debating their preferred exclamation when clinking glasses. Farhad, at 68 the elder statesman of contemporary Azerbaijani art, uses the Russian “Opa!” perhaps a carryover from his days roaming art circles in Soviet Moscow. Bahram, educated at New York’s Pratt Institute and a youthful 43, prefers the Scandinavian “Skål!”

Cultural ambiguities are common in this 23-year-old republic, fought over and occupied for centuries by Persians, Arabs, Mongols and Russians. In the past century alone, the national script has switched from Arabic to Latin, Turkic, Cyrillic and back to the present Turkic. But here in Baku, people are forging a new, vibrant identity and there’s much to look forward to. “Cheers!” we all agree as we drain our glasses.

Farhad, for one, is busy. The next morning he’ll depart for his mountain dacha to work on a series of ethereal landscapes. And in a week he’ll be back at his desk at the Union of Azerbaijan Artists, which he’s chaired since the last days of the Soviet era. It’s a big job. Azerbaijan’s nascent art industry is experiencing unprecedented attention.

Bahram does his part from the grassroots. His AZgallery liaises between Western and other buyers and Azerbaijani artists. His office, inside the crenelated walls of the wind-blown old city, is brilliantly placed for exploring other galleries that have grown up around this UNESCO World Heritage Site, like the Centre of Contemporary Art and Yay! Gallery, facing the sun-bleached 12th-century Maiden Tower.

Azerbaijan has, perhaps more than any other former Soviet republic, enjoyed a robust modern-art renaissance. When it gained its first, fleeting independence, in 1918, Azerbaijan was the Muslim world’s first democratic state. In the mid-20th century, the Soviets nurtured visual artists and sent legions to Moscow to study and exhibit.

In the 1970s, under the deified leader and trained architect Heydar Aliyev, artists began looking outward to their cohorts in Europe, gleaning new ideas from creatives in Hungary and Dresden and ultimately receiving political support. “Moscow played a big role in my life,” Farhad rasps through his luxuriant moustache. “The grand artists, the underground music concerts, the good times...”

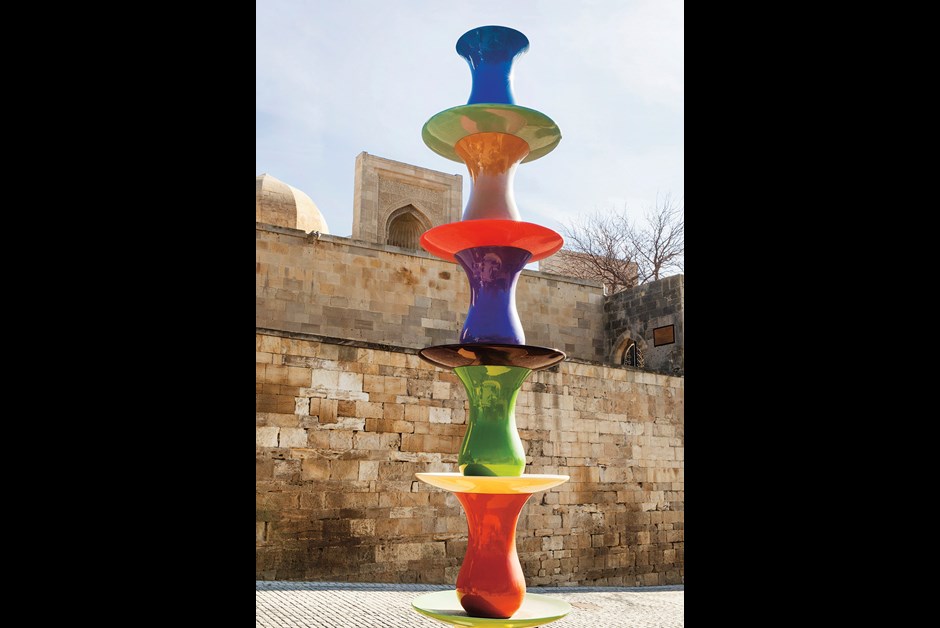

Evidence of this rich artistic history is everywhere in the revitalized city center, its vast beaux arts facades scrubbed to Monaco perfection, their interiors shrouded in hand-knotted silk rugs and elaborate tapestries. If you can negotiate the wide boulevards, where C-Class Mercedes are replacing the old Ladas at a remarkable rate, you’ll find a quirky street sculpture for every bronze statue of a statesman. Plus, there are more art museums than is plausible for a city of two million.

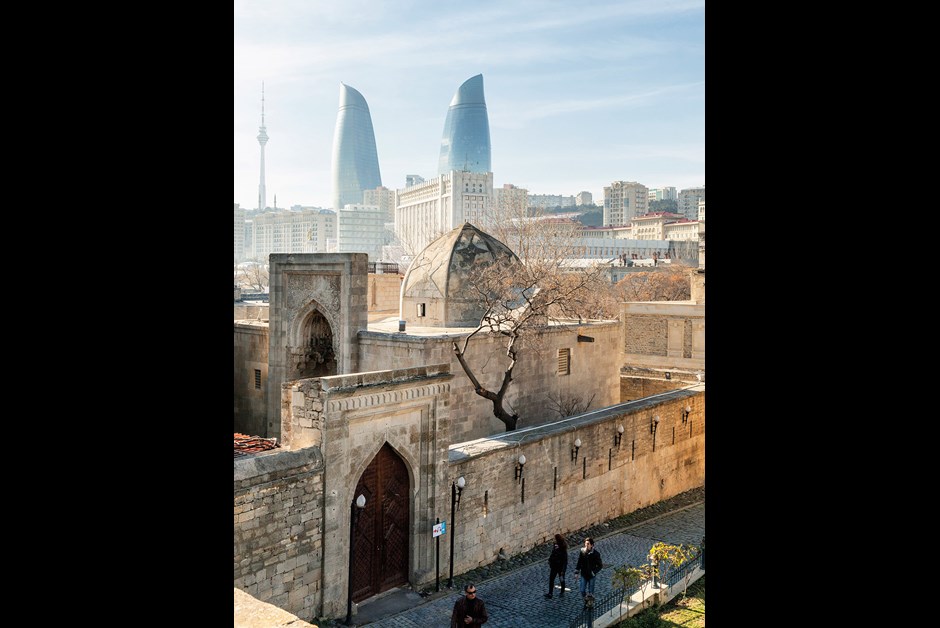

Baku is swiftly transforming from a Soviet outpost to a slick, fast-paced city with a dazzling future. Just two decades ago the resident “skyscrapers” were an unambitious nine stories. No sooner had the country gained its second independence, in 1991, than Baku reignited its plans for a TV tower on the crest of a hill that made its 1,000-plus feet appear more like the 2,700-pluss feet of Dubai’s Khalifa.

As any Bakili will tell you, though, the skyline’s most significant change is one you can spot from your plane’s approach. The Flame Towers, housing the Fairmont Baku, emblazon the city’s high ground with the national emblem. Called the Land of Fire, Azerbaijan got its name from natural gas reserves so abundant that flames literally spew from fissures in the earth – a phenomenon that likely inspired the Zoroastrians, or fire-worshippers, of the first millennium BC. The buildings’ architects at the London-based design firm HOK referenced this heritage with a trio of torch-like structures that light up after dark with thousands of LED luminaires embedded in the buildings’ skin.

The contrast between the new Baku, with its sinuous, iconic architecture, and the old, with its austere, 20th-century constructions, couldn’t be starker. In 2012, the fearless architect Zaha Hadid unveiled her colossal cultural center named for former president Heydar Aliyev, who brokered the country’s independence (and fathered current leader Ilham Aliyev). Otherworldly and startlingly white, it undulates like an arctic ice field. Meanwhile, at the water’s edge, the recently opened national carpet museum unfurls over a seafront park like Aladdin’s magic rug. Its Austrian architects, Hoffmann-Janz, achieved what has become the city’s modus operandi: a contemporary icon that references a millennium’s worth of cultural cues. A further showpiece is the work of architect Jean Nouvel: the Museum of Modern Art, where the vaulted white walls tell Azerbaijan’s story in works by experimental artists of the past 70 years.

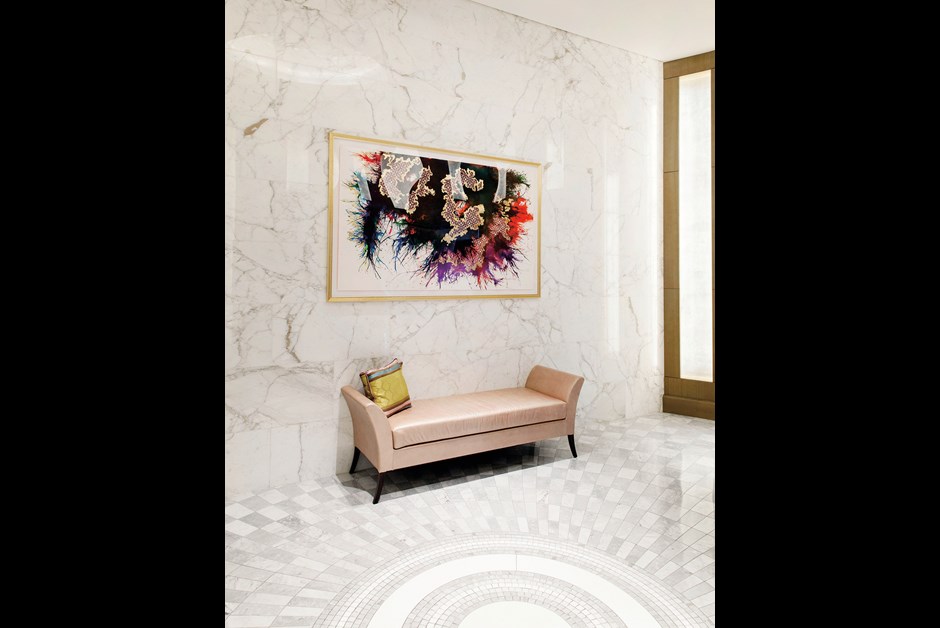

To really see how far the city’s art scene has come, take the free funicular up to the Flame Towers’ base. Fairmont Baku, occupying the northernmost building, developed its enviable art collection by acquiring work from local ateliers and international galleries alike. The objective was to offer a cultural experience to time-poor business travelers who might never have imagined the depth of the regional art world.

“Our collection is an authentic way to connect to the city,” says Ariel Grue Lee, business development director at Farmboy Fine Arts, an art consultancy, based in Vancouver, Canada, that curated the Fairmont’s collection. “Each piece has a specific story, which juxtaposes with the grand, luxurious surfaces.”

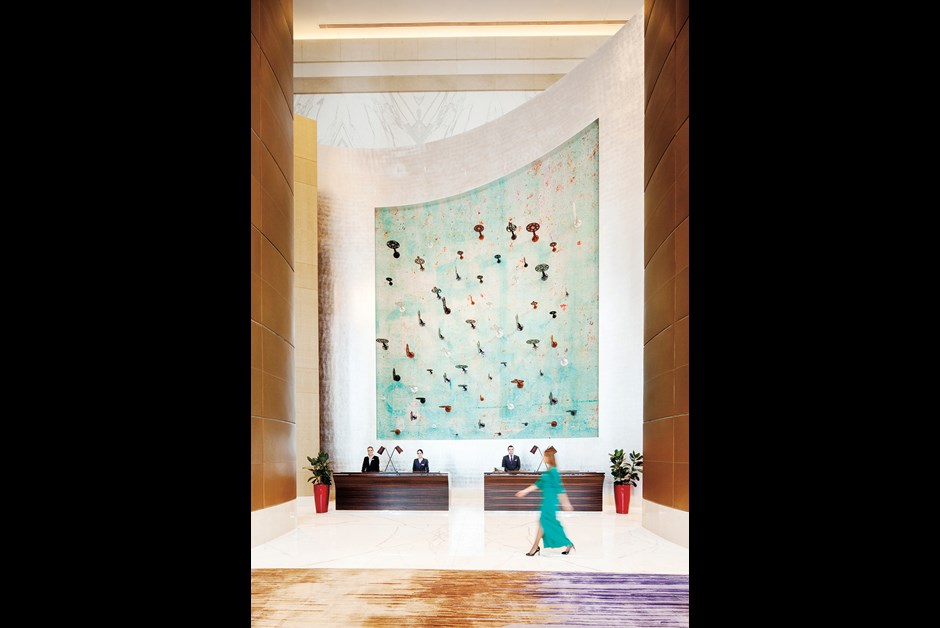

Also evocative of Baku’s cultural shift is the gracious interior by Hirsch Bedner Associates, both luxurious and rooted in the country’s artistic traditions. In the seven-story lobby, a Czech-designed chandelier with more than three miles of crystal-bead strands descends from a ceiling plastered in platinum leaf. And yet at eye level are delicate works of art that engage intimately with the viewer. Behind the reception desk, a vast contemporary installation incorporates dozens of architectural brass finials, or alems, found around the world, representing a coming-together of cultures and tribes.

You will not escape the art here, even in the elevators. Hanging in a corner of the lobby is Faig Ahmed’s “Restraint,” an ornamental “rug” that dissolves into running drips of paint. And on a plinth in the mezzanine is an irreverent bronze sculpture by Mahmud Rustamov. “That the collection is eclectic is important as well,” says Grue Lee. “It isn’t decorative. It could have been assembled over decades.”

Most of the artists in Farmboy’s stable are young “ones to watch,” but even the more established names are affordable. Collectors should act fast, too, because the profile of Azerbaijani artists is soaring. The most influential advocate of art in Baku has to be First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva, who heads the Heydar Aliyev Foundation, which supports the flourishing community. Every year the government invests in painting and sculpture for state buildings around the capital. And the non-profit Yarat Contemporary Art Space, founded by artist Aida Mahmudova in 2011, pursues lucrative sponsorships for exhibitions of Azerbaijani artists in venues like Yay! Gallery and even the Venice Biennale. “There’s a lot of money going into getting these artists exposed,” says Grue Lee, “and they have great people promoting them.”

On the top floor of a seven-story apartment block, equipped with its first elevator five years ago, Huseyn Haqverdiyev wrestles with a PC to scroll through digital images of his latest limestone sculptures, commissioned for a new park to the city’s north. He is the son of a successful propagandist and a veteran of the Baku arts scene who came up in the 1980s, an era of political support for new directions in art.

“In the old days,” he says, “we were trapped. Artists got money for creating portraits of Lenin, so that is what everyone wanted to do. Today it is much more experimental.” His modernist abstract paintings, inspired by the Russian avant-garde, hang in galleries and his epic mosaics can be seen at British Petroleum’s Sangachal Terminal on the Caspian shore. Between orders he targets every surface of his warren, stripped back to the studs, with thick splashes of paint, inspired by the view – domes and minarets in the middle distance and, beyond, the sea stretching out toward Turkmenistan.

As recently as 2012, when he traveled to London to show in the Fly to Baku exhibition at the Phillips de Pury gallery, Haqverdiyev couldn’t have imagined how little time he’d have for house painting. Last year he was the focus of an exhibition at Yay! and shortly thereafter he sold three works to the collection at Fairmont Baku. When I ask him if he advises other artists – like 36-year-old Emin Asgerov, who, in a studio down the hall, paints vast, emotional canvases celebrated in exhibitions from Tashkent to Turkey – he chortles and with a dramatic sweep of his hand declares: “Of course,” like the godfather of this increasingly influential family.

He was taught well. His friend and mentor Farhad Khalilov spent generations fighting for the freedoms enjoyed by his contemporaries. Eventually Khalilov lived to see his boom. And as he offers me a lift back to the hotel I notice he’s got the Land Rover to prove it.

Artist

faig AHMED

My favorite place… Ateshgah fire temple. It inspires me because it’s one of the most ancient places here. It was constructed and added to by different cultures in different ages, which is proved by the Sanskrit writings on the walls and other ancient symbols.

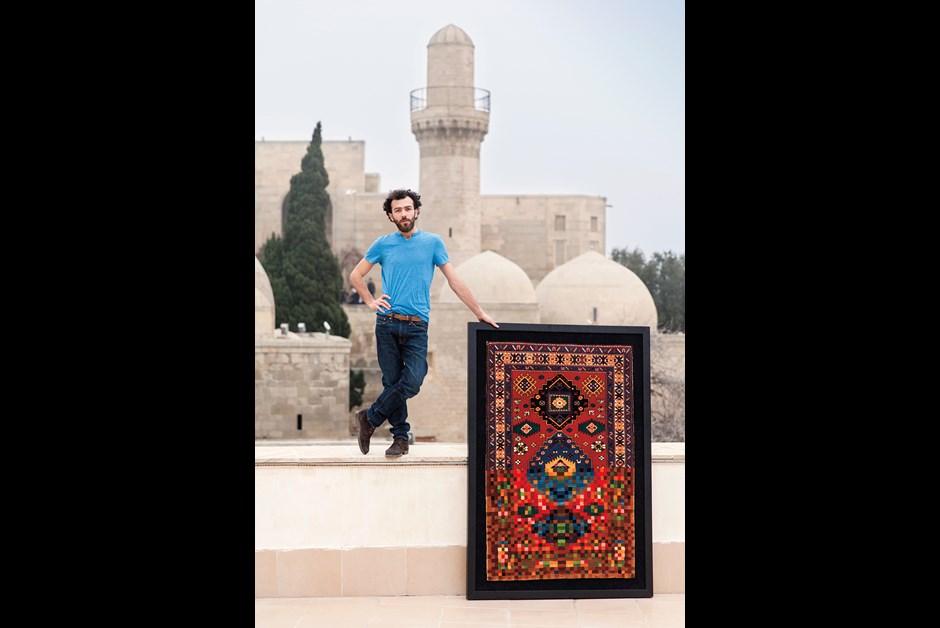

clockwise from top left: The baku eye observation wheel stands 200 feet (60 meters) tall; The ateshgah Fire temple is located in the suburb of surakhani where natural-gas-fueled fires once erupted spontaneously from the ground; artist faig ahmed holds up "pixelate tradition," one of his works in handmade woolen carpet; the lobby of fairmont baku, featuring "Unions," a work by farmboy fine arts

Artist

SITARA IBRAHIMOVA

My favorite place… Baku Boulevard. This is probably the only place in the city where you can just spend time alone with your thoughts while walking in the park and enjoying the sea.

clockwise from top left: Photographer Sitara Ibrahimova, part of the Yarat art collective, at le Café in the old city; view of baku boulevard and the world's tallest flag at 230-by-115 feet (70-by-35 meters); the lobby of the fairmont baku features a towering crystal chandelier; exterior of the heydar aliyev cultural center; "Seven Beauties" teacup sculpture by Nail Alakbarov near the old city wall; The rolled-tapestry-inspired State museum of azerbaijani carpet and applied arts

Left and Below: original artwork at the fairmont baku, including "10750 Pages" by Iranian artist Hadieh Shafie (made up of thousands of rolled-up farsi texts) and "Untitled (three moons)" by Egyptian-canadian artist sherin guriguis; Above: A room with a view of the city and caspian seafront at Fairmont baku

On the cover

Artist

FARID RASULOV

My favorite place… The old city. Poets and writers are often inspired by its timeless beauty. Artists have been dwelling in this area for years. Some are so fortunate as to own a studio amidst ancient minarets and mosques. The atmosphere here draws you in right away and infuses you with creative energy. As I wander these streets, I become more and more aware of who I am: an artist and a dreamer.

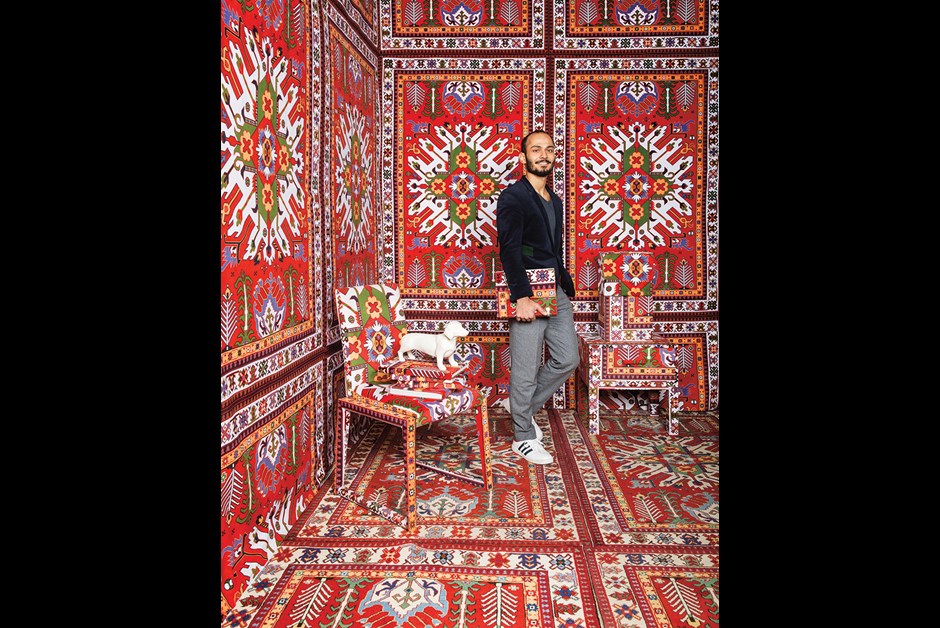

we photographed artist Farid Rasulov in his work "Carpet interior." The installation, a room papered entirely in printed textiles, had just returned to baku from the 2013 Venice Biennale. much to our surprise, Rasulov, who also designs a clothing line called Chelebi (a blazer from the collection is pictured, right), offered to fashion a suit from the same material. What else could we say, but "Yes, Please!" See the installation as it is being constructed and more images of baku at everyonesanoriginal.com/fairmont-magazine

Concierge Baku, Azerbaijan

Stay Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers, is an architectural monument, art museum and hotel in one, located at the city’s highest point and visible for miles (an added benefit: you'll never get lost). A free funicular takes you from the waterfront to the complex, which is equipped with an ESPA spa facility set over two floors, and indoor and outdoor pools with views across the old city. For an exclusive lifestyle

hotel experience, a stay on the Fairmont Gold floor promises special privileges and extra-attentive service, designed to meet the needs of the most discerning guest.

fairmont.com/baku

Dine Within the Fairmont Baku, fashionable Bakili congregate at Alov Steakhouse, a contemporary dining room with a southwestern American theme and an open kitchen headed by chef Orkan Mukhtarov. They also head to the Alov Jazz Bar, which features live music every evening (Baku is a regional center for jazz), along with light bites and classic cocktails. Designers Hirsch Bedner Associates kitted out the Nur Lounge with a bar of textured champagne glass and a cutting-edge

M. Liminal grand piano by Fazioli.

Do Meander through the old city to shop for fine carpets, silk scarves and shaggy lambskin hats, a Bakili tradition. Or drive southwest to Gobustan, where pre-historic peoples embellished their environment with a rich cache of petroglyphs, discovered by quarry workers in the 1930s.